Frequently asked questions about bioinformatics

These are my attempts at answering some of the questions I see come up on the r/bioinformatics sub-reddit or questions I get asked in real life about the field. These answers are my opinion only, are subject to change and should be taken with a grain of salt. This post was first written in September 2015 and updated some minor changes in October 2017.

What is ‘bio-informatics’?

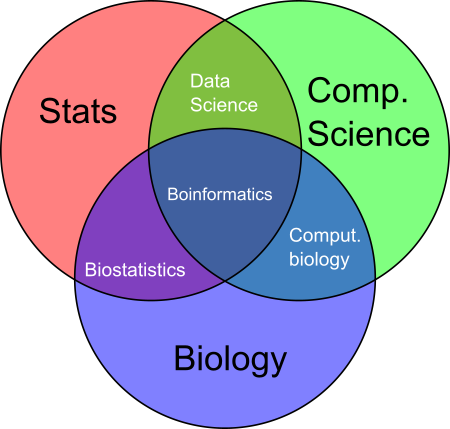

Whenever I mention that I’m in the field of ‘bioinformatics’, I either get a nod of recognition or a look of utter puzzlement as my conversation partner tries to parse the sheer number of syllables I’ve thrown their way. Some think I’m involved in engineering bio-mechanical devices (which is the completely different field of biomedical engineering), or that I am splicing genes to create some kind of mutant super-army. (Which is actually just a part-time hobby of mine and totally unrelated to bioinformatics, but I digress…) The definition can be elusive, but it can be (vaguely) defined as an area of study on the intersection between molecular biology, computer science and mathematics. It’s everything from the human genome project to studying how cancer evolves and mutates. You can get a better idea by reading about some cool projects that involve bioinformatics:

- ENCODE - how bioinformatics is helping us to understand the features of the DNA landscape

- Connectome project - how bioinformatics will transform our knowledge of the brain

- Discovering our inner neanderthal - what bioinformatics can tell us about our ancestry

What’s it like being a bioinformatician?

It depends on what kind of bioinformatician you are. I like to think that there’s two main ‘classes’ of bioinformatician. There are those who are concerned mostly with the biological questions, and computers and stats are just their tool of choice–they might be a wet lab biologist who has picked up enough R, python or perl to be dangerous, or they’ve started out in the dry lab (this is what us bioinformaticians call our work desk) but are interested in solving chiefly biological problems. They may spend a lot of time generating experimental data the old fashioned way with a pipette, or they may never set foot in a wet lab at all. They will generally use existing methods and techniques to analyse their data when they’re in the dry lab. Their focus is largely on the bio of bioinformatics.

Then there are those bioinformaticians who work on developing new statistical or computational methods. This might be because they are attempting to answer a biological question and no appropriate method exists, or they are trying to fix artefacts or noisy signals that creep into the data. They typically spend more time writing code, developing new software and methods. Their focus tends to be more on the informatics part of bioinformatics.

All this means that it’s hard to pin down the typical bioinformatician! You could be anywhere from a pure biologist who dabbles in the informatics side, or a theoretical statistician who’s work may have some biological application. Day to day, a typical bioinformatician may be developing software, parsing data (I think most would agree that we collectively spend too much time on this), scribbling statistical models on a white-board or stepping into the wet lab to prepare some biological data for sequencing.

How do I get into the field?

There are many answers to this question. Personally, I studied a master’s degree in science, specialising in bioinformatics. Before this, I completed a computer science undergraduate degree and worked in IT as an analyst programmer. But you don’t have to study bioinformatics specifically; plenty of people that get into the field have taken non-traditional routes. Many bioinformaticians come from backgrounds as diverse as physics or astrophysics, mathematics, computer science or statistics–essentially if you can wrangle data, write code and think scientifically, you can get into the field.

While undergraduate and master’s level courses in bioinformatics are much more common now than they were a few years ago, you can still enter the field by studying computer science, statistics or biology to a research-intensive level, and taking on a bioinformatics project to gain experience in the area. People coming from a single area often benefit from taking electives in whichever area they are missing a foundation in (within computer science, statistics and biology). There are also plenty of self-directed courses that offer a grounding in these areas, although, being ‘self directed’ require a good deal of time, dedication and discipline to utilise most effectively.

In general, research experience is the most valuable asset to getting into the field – especially research experience in quantitative projects. This usually means having an honour’s or master’s degree. Only labs or institutes that require dedicated developers to work on their biological software may hire those coming straight from undergraduate degrees. Generally, there are few positions available to someone with solely a bioinformatics bachelor’s degree. To get into the academic side of the field, you will want to obtain bioinformatics research experience in an honour’s, master’s or PhD programme.

What’s the pay like?

In my original post, I gave some ball-park figures for bioinformatics salaries which prompted some discussion on Reddit. There are some pay-scale websites (for example this one) that will give you more up-to-date statistics than my speculation can provide. Keep in mind that salaries in bioinformatics will vary greatly by where you live, so make sure you research pay scales in your area.

That said, bioinformatics is not something you do for the money. There are plenty of positions in data science or software engineering that require similar skills, pay far more and offer greater job security. Bioinformatics is something you should do because the work genuinely excites you. As tenure-track and lab head positions are highly competitive, usually requiring an A-star publication record, it is worth learning about the state of career progression in academia and plan your career accordingly.

Where should I look for a bioinformatics job?

Most bioinformatics jobs won’t be advertised on your job search engine of choice. It’s currently a small field with a tight community (but growing fast), so your best bet is to get involved with a bioinformatics student group, go to conferences and engage with the community in your area. Obtaining a research placement in a research lab (a requirement for some bioinformatics degrees) is a great way to get your foot in the door and demonstrate your capacity to take on work in the field. This could even lead to an offer of employment if you make a good impression.

What are the best things to learn if I want to get into the field?

This really depends on what specialty you want to be in or role that you want to work in. If you’re not sure and you want a broad experience base, learning these could be helpful:

- Basic statistics, probability theory, set theory: get as solid grounding in these as possible.

- Basic molecular biology: get yourself a copy of Molecular Biology of the Cell.

- R programming, and/or a scripting language: Python is popular and easy to learn, Perl is another option that was once standard in bioinformatics, however its popularity has declined markedly in the last several years.

- UNIX/basic shell scripting: invaluable for quickly manipulating files and writing simple pipelines.

These are the basic building blocks but only the first steps in a massive field. To be in bioinformatics, you have to constantly learn as the field moves rapidly. As you get more experience, it’s worth thinking about your particular specialty that you bring to the field. Are you good at working with algorithms? Modelling complex biological systems? Having an encyclopaedic knowledge of an area of the literature? Identify an area and build your skills – it will make you stand out. Also realise that you can’t know everything; true experts in the biological and computational and statistical ends of the spectrum are exceedingly rare – and it’s always better to know one area in great depth, rather than several areas shallowly.

Should I get a PhD?

That’s a question only you can answer. If you desire to lead projects it would be difficult to progress far without a PhD in an academic or research-based setting. On the other hand, if you are chiefly interested in the coding side, a PhD is not required for research assistant (RA) type positions, and a master’s or honour’s will generally suffice. RA work may involve more ‘grunt’ work and being delegated tasks, but this might not be the case depending on the lab you work for. Some RA positions may be more of a ‘bioinformatics programmer’ role where the emphasis is more on implementing reusable bioinformatics software. PhDs and higher-level positions generally involve more freedom and ability to choose one’s research direction. Some people also can’t stand reading papers or writing them–which will also be a significant hurdle to overcome if you want to do a PhD. Financially, a PhD may not be a good short-term investment, but whether it is a good long term investment is up for debate. If you are considering a PhD, do it for the intangible reasons that will make your career more rewarding. Do it because you are passionate about the area–because you want to learn how to solve big open-ended problems–and/or because you want to contribute to humanity’s scientific knowledge.

Are there positions in industry?

It depends where you live. In Australia, there are few such positions, but they do exist (IBM for instance has a life sciences division). Once companies figure out business models that make bioinformatics businesses viable, there’s a good chance many more bioinformatics start-ups will emerge. Currently though, unless you are in the US, UK or parts of Europe or Asia (e.g. Germany, South Korea or Singapore) bioinformatics jobs in industry are scarce.

Is bioinformatics a viable career path?

That depends on your perspective. Because the area is highly inter-disciplinary, the skills you learn are largely transferable to data analysis/big data science and software-engineering/programming roles. Within academia, it can be a rewarding and viable career path, yet academia has hardly done enough to create career paths for early career bioinformaticians. Of course, in terms of pure ‘work’, there’s plenty of it out there – just the number of funded positions don’t match. So when you hear ‘We don’t have enough bioinformaticians!’, this essentially means ‘We’d love a bioinformatician! Wait we have to actually pay them? Ah… on second thoughts let’s just throw together some old Perl scripts…’

What is the future of bioinformatics?

Future predictions about the field are generally lofty and probably inaccurate. As mere mortals, we are generally really bad at predicting the future. I see bioinformatics growing and integrating itself more strongly in areas outside of research, such as personalised medicine, and services direct to the public (think 23 & Me). The main short-term obstacles right now largely depend on political climate and government funding, which is eternally cyclical.